HomeNews & Events2013October Decoding the Wordless World of...

One of the leading comic scholars in North America seeks to unpack the origins of wordless comics to get a better understanding of how we interpret visual information.

Whether you are a fan of Owly or Tintin, comics have been a source of reading pleasure for children and adults for many years. Now, one of North America’s leading comic scholars will explore a form of this popular genre -- called silent comics -- in a two-year research project at Ryerson University Faculty of Art’s Modern Literature and Culture Research Centre.

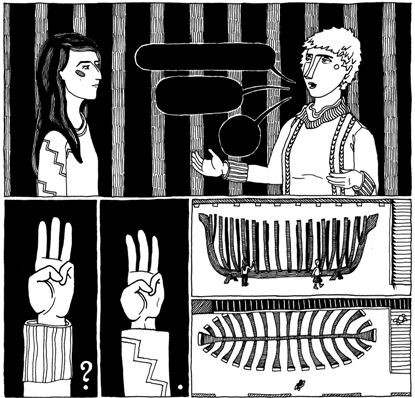

Silent comics use images to tell their story without the help of dialogue or words. Barbara Postema will deconstruct their origins and study the visual communication of this art form, in a project that spans works from North America, Western Europe, Australia and Japan.

"What silent comics show is visual communication, and that is something that goes on around us all the time,” says Postema, who is one of a handful of scholars studying silent, or wordless comics, in North America. "Silent comics contain these moments and capture them in only a few panels. Studying this art form is one way of understanding how we can interpret visual information.”"

Postema’s research reveals how readers make meaning through the visual, and how diverse cultures establish visual literacies that enable transnational understanding,” says Irene Gammel, Canada Research Chair in Modern Literature and Culture and a professor of English at Ryerson University. "Where verbal text may serve to create boundaries, images can be translated across different cultures, opening up circuits of mutuality and exchange.”

Funded by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada postdoctoral fellowship, Postema’s research will also focus on the cultural relevancy of silent comics from their origins in parts of Europe and Japan from the mid-1800s to present day. She is particularly interested in "visual culture”: the style and aesthetics of this comic form, how they tell a story without words and how silent comics are evolving.

"Earlier comics tended to be more detailed, more fine-art inspired,” notes Postema, "before they evolved into today’s more abstract style. Prior to the 1900s, pictorial narratives were used to tell stories, with traditions that date back to the Bible, or even farther.” The transition to comics, says the professor, came about in the early to mid 19th century when Rodolphe Töpffer, a Swiss cartoonist and author, revolutionized these picture narratives by placing images into panels and running them with text. "From there, there was a blossoming of people who started using this new form of storytelling.”

In addition, Postema will unpack the appeal of silent comics for children and adults. "For children, silent comics such as Owly offer a world that can be very different than our own, but one they can relate to and can read themselves. For adults, it’s sometimes nostalgia. They grew up with comics, so they still enjoy that feeling. Silent comics also involve the reader and makes them part of the story.”

Postema is inaugurating her research program by launching her first book, Narrative Structure in Comics, on Oct. 10 at the Modern Literature and Culture Research and Innovation Zone with a conversation with Ryerson English professor Andrew O’Malley. The book, published by Rochester Institute of Technology Press, decodes the world of comics: its narrative structure, the importance of gaps between panels, and how images and text work together to tell stories.

Postema’s research will culminate in the publication of a second scholarly monograph that traces the development of silent comics through the lenses of modernity, identity and gender. She also plans to curate an exhibition of contemporary woodcut novels, an art form that was very prominent in the 1920s and 30s and portrayed socially conscious stories in stark black-and-white images that inspired future silent comic art forms. Postema’s exhibition will showcase works by Toronto artists such as George Walker, Megan Speers and Marta Chudolinska, who work in the woodcut form today.

Suelan Toye

Public Affairs | Ryerson University