HomeNews & Events2009November A Changeable Feast

The Globe and Mail - From Saturday's Books section

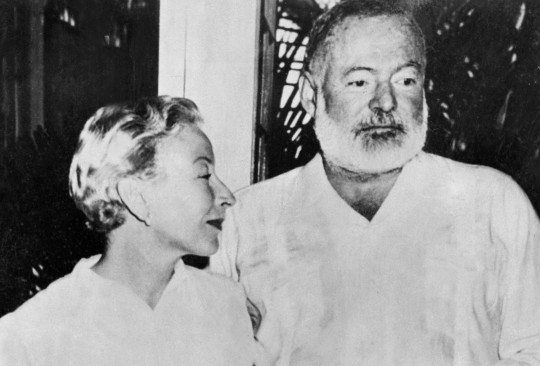

Ernest Hemingway with his fourth wife Mary, who edited A Moveable Feast and whose additions and deletions reflected her biases regarding her husband's earlier wives AFP/Getty Images

Ernest Hemingway's memoir of Paris was edited after his death by his fourth wife, who made changes that reflected her opinion of his earlier wives. Now Hemingway's original unedited version of A Moveable Feast is available, but does that really make it the 'correct' version?

By Irene Gammel

Published on Friday, Aug. 21, 2009

"All remembrance of things past is fiction and this fiction has been cut ruthlessly and people cut away,” Ernest Hemingway observes in A Moveable Feast: The Restored Edition (Scribner, 240 pages, $32.99). However, this new, ruthlessly cut version of Hemingway's Paris memoir has fuelled controversy, including a scathingly angry response by Hemingway's friend and biographer A.E. Hotchner ("Don't Touch ‘A Moveable Feast,'" The New York Times, July 20), who writes: “Scribner's involvement with this bowdlerized version should be examined as it relates to the book's actual genesis, and to the ethics of publishing.”

In 1920s Paris, Hemingway cut the figure of the quintessential American, attending the famous parties dressed in sneakers and a patched jacket. His fashion style, like his prose, was lean and stripped down. Posthumously published in 1964, Hemingway's classic memoir lovingly explores Paris as the city of great writers such as Gertrude Stein, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ford Madox Ford, James Joyce and Ezra Pound. Hemingway's eyes, ears, tongue and nose nostalgically linger in the Paris cafés (including the toilets!), hotels, lending libraries and salons, allowing us to see, feel, hear and taste how these spaces shaped his own style and identity as a writer.

The book is also a love story dedicated to his first wife, Hadley Richardson, but the happy tale of sex and experimentation ends in a tangled web of betrayal. Hemingway leaves Hadley for his second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer, who is presented as the wily intruder in the final chapters.

Now, Pauline and Ernest Hemingway's grandson, Seán Hemingway, has edited the restored version, giving Pauline a more sympathetic representation. But is this really a case of a literary classic being tampered with for the sake of a sentimental memory, as Hotchner charges? Not according to Seán, who asserts that the restored edition offers “a truer representation of the book my grandfather intended to publish.”

AP - Hemingway with his second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer, who was portrayed badly in A Moveable Feast after it was edited by Mary Hemingway, his fourth wife. Their grandson Séan is the one who restored Hemingway's original text.

In fact, for decades, scholars have talked about the tricky editing of A Moveable Feast by Mary Hemingway, Hemingway's fourth wife and, after his suicide in 1961, his executor. The unpublished papers at the John F. Kennedy Library reveal that not only was Mary's editing more substantive than just the insertion of a few overlooked ands and buts, as she had claimed, but also reflected her biases regarding her husband's earlier wives. She liked Hadley (who was amicable and still alive) and disliked Pauline (who, besides, had passed away in 1951).

Despite this tangled family web, however, Mary's version should be considered the definitive one, while the “restored” version provides access to important unpublished contextual sources that illuminate the evolution of the 1964 edition. It is here where both the title and the promotional material are raising questions about publishing ethics.

For example, while there certainly are some “never-before-published” gems in the “restored” version, they are largely found not in the memoir itself, but in the appendix titled Additional Paris Sketches, such as A Strange Fight Club, an intriguing portrait of Canadian boxer Larry Gains and his “jeux de jambes fantastiques”; and Secret Pleasures , a fascinating intimate account of Ernest and Hadley's erotic gender-bending delights, in which she cuts her hair short, while he lets his hair grow so they both have the same length. As Hemingway explains: “We lived as savages and kept our own tribal rules and had our own customs and our own standards, secrets, taboos, and delights.” At night, “one would wake the other swinging the heavy dark or the heavy silken red gold across the other's lips in the cold dark in the warmth of the bed.” These are Hemingway's discarded sections, never meant to be published, and therefore represent important texts that contextualize the original.

“Texts are not born, but are made, in a complex process of reader and institutional engagement across multiple generations. "

The restored memoir proper is based on Hemingway's unfinished typescript, which is missing its ending. As a result, in what now serves as the ending by default, the new edition gives unprecedented prominence to Hemingway's less-than-charitable treatment of his friend and rival, F. Scott Fitzgerald, as well as his wife, Zelda, who is portrayed as hawk-eyed, destructive, jealous and crazy. Not only does Fitzgerald require reassurance regarding the size of his penis (hence the title A Matter of Measurements, as the two men size up Scott's package in a restroom), but barman George at the Ritz delivers a fatal blow long after the Paris heydays are gone: “Papa,” he asks Hemingway, “who was this Monsieur Fitzgerald that everyone asks me about?” In Hemingway's man-coded universe, this is the mark of failure. (“I never met any one of his class who remembered him,” he had similarly written about the scapegoat figure Robert Cohn in his 1926 novel The Sun Also Rises.)

Contrast this portrait of rivalry, which Hemingway understandably was hesitant about considering as the final chapter, with the final sentence of Mary's 1964 version: “But this is how Paris was in the early days when we were very poor and very happy.” Here, Paris is the focus as the imaginary city capable of birthing new identities. Admittedly culled from a chapter Hemingway had discarded, Mary's ending, which also contains a cyclical turn from winter to spring, shows the steady hand of competent editors, including co-editor Harry Brague at Scribner's.

To be sure, giving readers access to Hemingway's original typescript is laudable, but when Hotchner talks about publishing ethics, what is really at issue is a rival version that is mass-marketed under the claim of being more authentic than the established one. The problem with this process has been illustrated by the test case of Theodore Dreiser's American masterpiece of naturalism, Sister Carrie , which received a similar make-over in 1981, restoring about 30,000 words along with the author's more sombre ending to create an “unexpurgated” edition mass-produced in a Penguin paperback. In the process, Sister Carrie lost her “innocence,” as Stephen C. Brennan has observed (in A Theodore Dreiser Encyclopedia): “It has roiled the critical waters, forcing readers into a choice that can never fully satisfy.”

The original U.S. edition

Ethically and pragmatically, restoring an author's original intent is a slippery slope when the published text has stood the test of time and when edits have been approved by authors or their legal representatives. For if we follow the logic of restoration to its extreme, should The Sun Also Rises have its first chapter restored, since its removal was clearly prompted by Scott Fitzgerald's forthright criticism of it (as shown in Michael Reynolds' biography)?

In truth, writing and publishing always involves editing, as spouses, friends and professional editors exert influence (Michel Foucault's concept of the “author function” usefully highlights the author as a composite), and a text receives its full authority through its reception by readers. Texts are not born, but are made, in a complex process of reader and institutional engagement across multiple generations.

Consider, then, a final irony. Readers may be surprised to learn that Hemingway considered calling his memoir The Early Eye and the Ear (How Paris was in the Early Days), an awkward title and most certainly a publisher's marketing nightmare, then and now. Mary turned to Hotchner, who supplied the fortuitous Hemingway quote: “If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man, then wherever you go for the rest of your life, it stays with you, for Paris is a moveable feast.”

The collaborative title stuck, standing proud even in A Moveable Feast: The Restored Edition – but thereby also forcefully contradicting Scribner's promotional claim, which advertises the book as “restored to the way Hemingway originally delivered it 50 years ago.” Instead, the restored edition has gone cherry-picking, accepting some of Mary's editing choices but not others.

Irene Gammel holds a Canada Research Chair in Modern Literature and Culture at Ryerson University in Toronto. She is the author of Baroness Elsa: A Cultural Biography and Looking for Anne: How L.M. Montgomery Dreamed Up a Literary Classic.